Mon Apr 7 2025

7:30 PM (Doors 6:30 PM)

$56.82

Ages 21+

Share With Friends

Lineup includes:

Bobby Bare Jr.

Jamey Johnson

Lucinda Williams

Emmylou Harris (singing with Buddy Miller)

Kendell Marvel

Todd Snider

Rodney Crowell

Mary Gauthier

Jamie Harris

Chuck Mead

Elizabeth Cook

Shawn Camp

Steve Earl

The Cowpokes

Buddy Miller

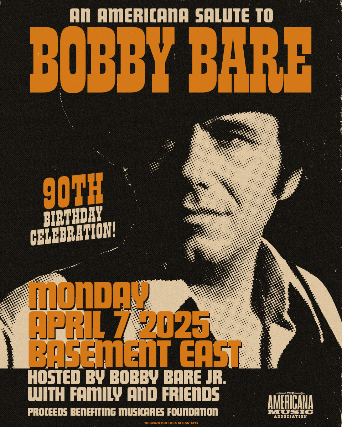

An Americana Salute to Bobby Bare - 90th Birthday Celebration w/ special guests Jamey Johnson, Emmylou Harris, Kendell Marvel, Lucinda Williams, Todd Snider, Buddy Miller, Chuck Mead, and more!

- SOLD OUT! All tickets to this concert have been sold. No additional tickets will be made available by the venue, artist, or promoter at any time. WE ONLY ACCEPT TICKETWEB TICKETS.

-

Bobby Bare, Jr. could’ve phoned in a career. He could’ve exploited the fact that he’s the son of iconic Country Music Hall of Famer Bobby Bare, was born into Nashville’s Music Row elite, and counted artists like Shel Silverstein as close family friends and George Jones and Tammy Wynette as next door neighbors. Instead, Bobby blazed a path of unique songwriting craftsmanship with a voice that blows through you like an unyielding wind on the desolate prairie.

With a big-as-the-room persona, an ability to rock the doors off the most jaded of clubs, the heart to hold a room completely still with just his guitar, and a genius for arrangement, Bobby Bare, Jr. and his band of merry makers are one of the most unique bunches around. They are adept at abandoning common sense in favor of laying themselves at the feet of a rambunctious, freewheeling, and unfettered and unhinged muse.

In the late 90's, he fronted the boss hog rock band, Bare Jr. With their two records,Boo-tay and Brainwasher, they memorably rocked out on a Nirvana-on-Skynryd-not-Sabbath groove, more indebted to the homebrew than "The Other H." He keeps himself even busier by appearing on albums by indie rock heroes like the Silver Jews and Frank Black and My Morning Jacket. Few that we have found can combine humor, pain, and anger in such an effortlessly well-crafted manner. If encountered in public, beware: Bobby is a big, gregarious, good-natured fellow who will giddily talk music (from the Smiths to Roger Miller to Metallica to Dolly Parton--sometimes in one breath) until the bartender is tossing you both out.

Look, we LOVE Bobby's records and we want people to hear them. Maybe our descriptions are making you scratch your head or are scaring you off. Forgive us, his music is ahead of its time and we are not sure what to say about it. All the years we all wasted getting English degrees are powerless in coming up with suitable words to describe his projects. When someone around the office is absent-mindedly whistling a tune, chances are real good that it's, "I'll Be Around" or "Valentine" or "Borrow Your Cape." Bobby's music is ample proof that commercial radio wouldn't know a genre-bending smash hit if it ran up and bit it in the ass, and, if radio programmers weren't all neutered corporate lapdogs, his songs would be in the broad canon of rock.

-

After leading several popular ‘80s cult bands in and around his hometown of Lawrence, Kansas, Chuck Mead landed on Nashville’s Lower Broadway where he co-founded the famed ‘90s Alternative Country quintet BR549. The band’s seven albums, three Grammy nominations and the Country Music Association Award for Best Overseas Touring Act would build an indelible bridge between authentic American Roots music and millions of fans worldwide. With BR on hiatus, Chuck formed The Hillbilly All-Stars featuring members of The Mavericks, co-produced popular tribute albums to Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings, guest-lectured at Vanderbilt University, and became a staff writer at one of Nashville’s top song publishers. In 2009, he released his acclaimed solo debut album, Journeyman’s Wager, and toured clubs, concert halls and international Rock, Country and Rockabilly festivals with his band The Grassy Knoll Boys.

As Music Director for the Broadway smash Million Dollar Quartet, Chuck began crafting the music arrangements during the show’s original Daytona and Seattle workshop productions, supervised the musical performances for its 2008 Chicago opening, created new music material for the show’s Tony Award-winning Broadway run, produced the original cast album, and oversaw the music for its smash 2011 premiere at London’s Noël Coward Theatre. In 2013, MDQ broke the Chicago record for longest running musical.

Chuck’s acclaimed 2012 release, Back At The Quonset Hut, was recorded at Nashville’s legendary Quonset Hut Studio where Patsy Cline, George Jones, Merle Haggard Roger Miller, Loretta Lynn, Johnny Cash and more cut some of country’s greatest tracks. Produced by original BR549 producer Mike Janas and with the participation of students from Belmont University’s College of Entertainment and Music Business, the album of classic covers features surviving members of Music Row’s original ‘A Team’ studio musicians as well as guest appearances by Old Crow Medicine Show, Elizabeth Cook, Jamie Johnson and Bobby Bare.

2014 ushers in Free State Serenade, the new Chuck Mead & His Grassy Knoll Boys release on Nashville-based Plowboy Records. Produced by long-time ally and friend Joe Pisapia (kd Lang, Ben Folds Five) and featuring BR549’s Don Herron, Old Crow Medicine Show’s Critter Fuqua, Alan Murphy, Will Rambeaux, and Mark Andrew Miller, Free State Serenade is Chuck Mead’s strongest effort yet.

“It’s been incredibly liberating to do all these things I’ve never done before. I’ve already gone from the bars of Lower Broadway in Nashville to the Broadway stage, and the upcoming album is one of the most unique and rewarding projects I’ve ever been a part of. I’m looking forward to where it all brings me next.” - Chuck Mead

-

Elizabeth Cook is a Nashville-based Singer Songwriter from Wildwood, Florida. As a critically acclaimed live act and recording artist, the New York Times lauds her “a sharp and surprising country singer”. A veteran SiriusXM Outlaw Country Radio DJ, hosting her own show, Apron Strings, nationwide for the last 10 years, she is also a favorite of David Letterman, a regular performer on the Grand Ole Opry, and a frequent guest star on Adult Swim’s long-running hit cartoon series “Squidbillies” on Cartoon Network.

In the words of the Drivin’ and Cryin’s legendary Kevn Kinney, “Elizabeth is so far ahead and under the radar you better have a supercharger for that fastback if you’re going to catch up! Enjoy the ride…”

-

-

Steve Earle, a man who doesn’t mind telling a story, was talking about the first thing Guy Clark ever said to him.

“It was 1974, I was 19 and I had just hitch-hiked from San Antonio to Nashville,” Earle said in mid-Texas-cum-Greenwich Village drawl. “Back then if you wanted to be where the best songwriters were, you had to go to Nashville. There were a couple of places where you could get on stage, play your songs. They let you have two drafts, or pass the hat, but you couldn’t do both.

“If you were from Texas, and serious, Guy Clark was a king. Everyone knew his songs, ‘Desperados Waiting For A Train,’ ‘LA Freeway,’ he’d been singing them before they came out on Old No. 1 in 1975.”

“So I was pretty excited when I went into the club and the bartender, a friend of mine says, ‘Guy’s here.’ I wanted him to hear me play. I was doing some of my earliest songs, ‘Ben McCullough’ and ‘The Mercenary Song.’ But he was in the pool room and when I go in there the first thing he says to me is `I like your hat.’”

While it was a pretty cool hat, Earle remembers, “worn in just right with some beads I fixed up around it,” Clark did eventually hear his songs. A few months later he was playing bass in Guy’s band.

“Now, I am a terrible bass player...but I was the kid, and that was what the kid did. I took over for Rodney Crowell. At that time Gordon Lightfoot’s ‘Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald’ was a top ten hit, which was amazing, a six and half minute story song on the radio. So Guy said, ‘we’re story song writers, why not us?’ So we went out to cash in on the big wave.”

The success of ‘The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald’ was not replicated, but Earle reports that being the 19-year-old bass player in Guy Clark’s band was “a gas.” At least until Earle went into a bar and left the bass in the back seat of his VW bug, from which it was promptly stolen. “It was a nice Fender Precision bass that belonged to Guy, the kind of thing that would be worth ten grand now. He wasn’t so happy about that.”

More than forty years later, Steve Earle, just turned 64, no longer wears a cowboy hat. “It was more than all the hat acts,” Steve contended. “My grandmother told me it was impolite to wear a hat indoors.” As for Guy Clark, he’s dead, passed away in 2016 after a decade long stare-down with lymphoma. But Earle wasn’t ready to stop thinking about his friend and mentor.

“No way I could get out of doing this record,” Steve said when we talked over the phone from Charlotte, North Carolina, that night’s stop on Earle’s ever peripatetic road dog itinerary. “When I get to the other side, I didn’t want to run into Guy having made the TOWNES record and not one about him.”

Townes van Zandt (subject of Earle’s 2009 Townes) and Guy Clark were “like Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg to me,” Steve said. The mercurial Van Zandt (1944-1997) who once ordered his teenage disciple to chain him to a tree in hopes that it would keep him from drinking, was the On The Road quicksilver of youth. Clark, 33 at the time Earle met him, was a longer lasting, more mellow burn.

“When it comes to mentors, I’m glad I had both,” Earle said. “If you asked Townes what’s it all about, he’d hand you a copy of Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. If you asked Guy the same question, he’d take out a piece of paper and teach you how to diagram a song, what goes where. Townes was one of the all-time great writers, but he only finished three songs during the last fifteen years of his life. Guy had cancer and wrote songs until the day he died...He painted, he built instruments, he owned a guitar shop in the Bay Area where the young Bobby Weir hung out. He was older and wiser. You hung around with him and knew why they call what artists do disciplines. Because he was disciplined.”

“GUY wasn’t really a hard record to make,” Earle said. “We did it fast, five or six days with almost no overdubbing. I wanted it to sound live...When you’ve got a catalog like Guy’s and you’re only doing sixteen tracks, you know each one is going to be strong.”

When he was making TOWNES, Earle recorded “Pancho and Lefty” first; it was a big record, covered over by no less than Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard and Bob Dylan. “You had to go into the bar and right away knock out the biggest guy in the room,” Earle recalled.

With GUY it was a different process. Clark didn’t have that one career-defining hit, but he wasn’t exactly unknown. “Desperados,” “LA Freeway” were pre-“Americana” style hits. “New Cut Road” charted for Bobby Bare and was recorded by Johnny Cash. “Heartbroke” was a # 1 country record for Ricky Skaggs in 1982. But when you added it up, Clark’s songs wove together into variegated life tapestry, far more than the sum of the parts.

Earle and his current, perhaps best ever, bunch of Dukes take on these songs with a spirit of reverent glee and invention. The tunes are all over the place and so is the band, offering max energy on such disparate entries as the bluegrass rave-up “Sis Draper” and talking blues memoir of “Texas 1947.” Earle’s raw vocal on the sweet, sad “That Old Time Feeling” is heartbreaking, sounding close enough to the grave as to be doing a duet with his dead friend.

You can hear little hints of where Earle came from. The stark “Randall Knife” has the line “a better blade that was ever made was probably forged in Hell,” which wouldn’t be out of place in a Steve Earle song. Also hard to beat is “The Last Gunfighter,” a sardonic western saga to which Earle offers a bravura reading of the chorus: “the smell of the black powder smoke and the stand in the street at the turn of joke.”

But in the end GUY leads the listener back to its beginning, namely Guy Clark, which is what any good “tribute” should do.

Indeed, it was a revelation to dial up a video of Guy Clark singing “Desperados Waiting For A Train” on Austin City Limits sometime in the 1980’s. Looking as handsome as any man ever was in his bluegrass suit and still brown, flowing hair, Clark sings of a relationship between a young man and an older friend. Saying how the elder man “taught me how to drive his car when he was too drunk to,” the young narrator describes a halcyon fantasy in which he and friend were always “desperados waiting for a train.” As time passes, however, the young man despairs. To him, his friend is “one on the heroes of this country.” So why is he “dressed up like some old man?”

Steve Earle delivers these lines well, as he always does. But the author of “Guitar Town,” “Copperhead Road,” “Transcendental Blues” and a hundred more masterpiece songs, would be the first to tell you it is one thing to perform “Desperados Waiting For Train” and another to be its creator. There are plenty of covers better than the original. But “Desperados...” will forever reside with Guy Clark, the songwriter singing his song, just him and his guitar. That is the main thing GUY has to tell you: to remember the cornerstone, never forget where you came from.

There was another reason, Earle said, he couldn’t “get out of” making GUY. “You know,” he said, “as you live your life, you pile up these regrets. I’ve done a lot of things that might be regrettable, but most of them I don’t regret because I realize I couldn’t have done anything else at the time.”

“With GUY, however, there was this thing. When he was sick---he was dying really for the last ten years of his life---he asked me if we could write a song together. We should do it ‘for the grandkids,’ he said. Well, I don’t know...at the time, I still didn’t co-write much, then I got busy. Then Guy died and it was too late. That, I regret.”

Earle didn’t think making GUY paid off some debt, as if it really could. Like the Townes record, Guy is a saga of friendship, its ups and downs, what endures. It is lucky for us that Earle remembers and honors these things, because like old friends, GUY is a diamond.

-

-

-

-

-

Acclaimed solo artist. Grammy-winning songwriter. Road warrior. By the time Kendell Marvel moved into a 200 year-old farmhouse in the Tennessee countryside in 2021, he'd already spent more than two decades expanding the boundaries of modern-day country music.

Albums like Lowdown and Lonesome and Solid Gold Sounds were showcases for his blend of southern twang and super-sized vocals, filled with songs that split the difference between honky-tonk country and roadhouse rock & roll. Marvel's catalog reaches far beyond his solo work, too, with artists like George Strait, Gary Allan, and Chris Stapleton all landing Top 40 hits with his compositions. The man had clearly left his mark. If he'd chosen to celebrate his new home by taking a few months off, the vacation would have been well-earned.

Of course, you can take the man out of Nashville, but you can't take the Nashville out of the man. Hours after moving in, Marvel unpacked his guitars and quickly got to work in his new space, writing songs that blended timeless textures with contemporary insight. He began with "Younger Me," a nostalgic ode to young manhood and resilience that became a Grammy-winning hit for the song's co-writers, Brothers Osborne. He kept writing during the months that followed, fine-tuning the mix of country-rockers, soul standouts, and bluesy ballads that now fill his third solo effort, Come On Sunshine.

Recorded in Dallas, TX, with producer Beau Bedford — ringleader of The Texas Gentlemen, as well as the sonic architect behind albums by Paul Cauthen and Leah Blevins — Come On Sunshine burns as brightly as its name. These are songs for Saturday night hell-raising and Sunday morning comedowns. They're stand-your-ground anthems and help-your-neighbor rallying cries. They're sharply-written tunes about booze and breakups, true love and false prophets, bad habits and proud traditions, delivered by a songwriter who's lived enough life to confidently chronicle its ups and downs.

"I'm 51 years old, which means I'm long past the point of catering to anybody," Marvel says. "I'm just telling the stories I want to tell, whether it's a song like 'Come On Sunshine' — which Devon Gilfillian and I wrote at the height of the pandemic, looking to pour some light into the people who were shut in, shut down, and struggling with the doom and gloom we were all seeing on TV — or “Keep Doing Your Thing,” which argues that the world would be a better place if we just let people be who you are."

He even zeroes in on money-hungry televangelists with "Put It In The Plate," a southern-fried stomper that's already become an audience favorite during Marvel's ongoing tours with Chris Stapleton. "It's got that sound I grew up loving, like Hank Jr's songs in the '80s," he explains. "It's not country, it's not rock; it's just a perfect mixture of all of it. It's an interesting song because it's calling out the righteous gemstones of the world! Maybe it'll piss people off, but sometimes, the truth does that."

The truth goes down a little easier when it's set to a soundtrack of greasy funky-tonk and nuanced Tennessee twang, though. At its heaviest moments, Come On Sunshine leans closer to the rock & roll side of the country-rock divide, with Marvel delivering amplified anthems like "Don't Tell Me How To Drink" with the gruff growl of a lifer who's earned the right to call his own shots. "Brother, I've spilled more on the barroom floor than you've ever had, so let me do my thing," he barks in his deep baritone, backed by cymbal crashes and ringing power chords. If those moments nod to the ZZ-Top-meets-Merle-Haggard sound of his Keith Gattis-produced debut, Lowdown and Lonesome, then tracks like "Hellbent on Hard Times" and "Dyin' Isn't Cheap" salute the vintage warmth of 2019's Solid Gold Sounds, which Marvel recorded with The Black Keys' Dan Auerbach. Come On Sunshine finds the middle ground between those two records, its diversity mirrored by Marvel's broad list of collaborators.

Auerbach makes another appearance, this time as the co-writer of the piano-driven drinking song "Off My Mind." Mickey Raphael, longtime harmonica player for Willie Nelson, adds atmosphere and ambiance to "Dyin' Isn't Cheap," while Stapleton serves as a co-writer and backing vocalist on two tracks. Finally, solo artists like Dee White, Waylon Payne, Dean Alexander, Kolby Cooper, NRBQ's Al Anderson, and Josh Morningstar all contribute to the remaining songs. Such a lengthy guest list brings with it a number of different perspectives, which Marvel insists is the whole point.

"I like to work with people who are different than me," he notes. "Working with Beau Bedford in Dallas meant that I was playing with guys I'd never met before. Guys who had different ideas, different tones, and different ways of playing than my friends back home. We recorded the album live, finishing the whole thing in four days. That's how you capture magic. The same thing can be said for the people I write with. I prefer left-field people — people who come from different backgrounds and different genres. Devon Gilfillian comes from the R&B world; he hears different melodies than I do. Waylon is a gay man, so he has some experiences that are different than mine. I love to surround myself with people like that, and sit in the writing room with someone who isn't just like me. Because that's how you capture magic, too."

It's been nearly 25 years since Marvel — a native of southern Illinois, where he began playing barroom gigs at 10 years old — moved to Nashville and wrote Gary Allen's Top 5 hit "Right Where I Need To Be" during his first day in town. With Come On Sunshine, he proves that one's day in the sun can last a lifetime, as long as you're willing to listen to the muse, challenge your perspectives, and chase down the magic in front of you.

-

-

Rodney Crowell – Career Bio Great songwriters are said to reveal themselves through their work; their candor and transparency of soul is the key to the listener’s empathic heart and the culture’s admiration. But the lions of country songwriting, idolized and covered in magazines as they are, can sometimes feel like statues carved in marble, not fleshy, visceral human beings who’ve been scared, scarred and small just like us. And that’s why Rodney Crowell, who completed an astonishing personal pilgrimage from great American songwriter to laudable author with his 2011 memoir “Chinaberry Sidewalks,” stands apart. We meet in those pages someone we thought we knew: the wiry and slender guitarist in Emmylou Harris’s first Hot Band, the young protégé of Guy Clark and Mickey Newbury, the icy cool country star and Grammy winner of the 1980s, the longtime professional partner and husband of Rosanne Cash, the Cherry Bombs bandmate of Vince Gill and Tony Brown, the comeback kid of the 2000s whose incisive, quasi-autobiographical album cycle secured him a Lifetime Achievement Award for Songwriting from the Americana Music Association. But in “Chinaberry Sidewalks,” his acclaimed book, we get a portrait of the artist as young man and boy, a story that’s more than incidental to the artist he’d become. We recognize the wrinkles and complexities and wounds that would make his lyrics so relatable and shaded. We discover why Crowell has said that in the genetic mingling of his articulate, word-loving mother and his country musician father, he believes he was born to write songs. Crowell’s work and career sets a benchmark for commercial success and lifelong artistic ambition and integrity in country music. His compositions, including “Til I Gain Control Again,” “I Ain’t Livin’ Long Like This,” “Song For The Life” and “Ashes By Now” have been widely and successfully covered by legendary singers. But he led the way as a recording artist, achieving a dazzling run of radio hits in the 1980s, followed by a series of more personal albums in the 2000s that secured his place as much more than a chart topper. He’s had songs as an artist or writer in the top ten in every decade since the 1970s, including latter-day landmarks “Please Remember Me” and “Making Memories of Us.” He’s a Grammy Award winner, a member of the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame and the recipient of the 2009 Lifetime Achievement Award for Songwriting from the Americana Music Association. Born in 1950, Crowell’s life is framed by the most dynamic, prosperous and fraught half century in American history and music. He is the son of a proud, prickly and self-defeating father who starts a honky tonk band, fueled by a love of great songs and poignant delusions of grandeur. His mother is a devout Christian who sacrifices to hold a marriage and family together under a leaky roof in the tropically hot and wet suburbs of Houston. Rodney is resilient, resourceful and giving, whether going to extremes in attempts to de-fuse explosive fights between his parents or holding his mother during epileptic seizures. His father presses eleven-year-old Rodney into service as the drummer in his rag tag band J.W. Crowell And The Rhythmaires. There, Rodney internalizes the vast catalog of classic songs his father has in his otherwise disorderly head. Also around this time, J-Bo, as his father calls himself, takes Rodney to a package show held in ominous weather at the Magnolia Gardens Bandstand in Channelview, Texas featuring Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis and Johnny Cash. Somewhere between the hot rhythm, the thunderous downpour during Lewis’s set and the commanding presence of Cash, Rodney Crowell’s compass finds a new North. Crowell forms his first band in high school and then dabbles with college in Nacogdoches, Texas while playing barroom covers and experimenting with writing songs. His roommate Donovan Cowart is a collaborator and a conduit to the next step, because his brother, Walter Martin Cowart, is a poet and a trucker who passes through town occasionally, sharing his wisdom and his notebooks. Inspired by these talismanic first drafts and jottings, Rodney taps into the romance and allure of the writer’s life. Walter Cowart would go on to write “One Paper Kid,” which was recorded by Emmylou Harris and others. Rodney and Donovan make a recording together in Crowley, Louisiana that becomes a pretext to Rodney’s migration to Nashville in 1972. Crowell is drawn as if by gravity to the small, fiercely independent and artistically minded clique surrounding Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, Mickey Newbury and several others whose standards in songwriting are both daunting and inspiring. Crowell embraces their ethos, and he’s a quick study in his new “society of song.” But in early ‘70s Music City, outlets are few. His low paying happy hour gig at the Jolly Ox has a rule against singing original material. One evening, when Music Row kingpins Jerry Reed and Harry Warner are in the bar, Rodney says to hell with that and sings a 24-hour old song called “You Can’t Keep Me Here In Tennessee.” The bar owner fires him, but Warner offers to record the song the next day. Crowell is invited to the session, and when he arrives early at RCA Studio A, he meets Chet Atkins, who takes an interest in the gobsmacked lad and shows him in detail around the studio. The spark of that day leads to a publishing deal and a modicum of stability. Crowell writes a number of songs in his early 20s that will become his classics, thanks in large part to the perceptive respect and engagement of Emmylou Harris. The new country star records “Til I Gain Control Again,” which leads to their meeting. After he plays rhythm guitar with her in Austin one night, she invites him to move to California in 1975 to join her Hot Band, beginning a lifelong relationship that’s proven one of the most fruitful and enriching in Americana music. Harris becomes but one of many artists who record Crowell songs. Even before launching as a recording artist himself, his songwriting is widely acknowledged. Things move faster. He launches the band The Cherry Bombs with friends Vince Gill and Tony Brown, both of whom are destined for stardom in various sides of the music business. Crowell is signed to Warner Bros. Records and releases his solo debut album Ain’t Living Long Like This. A year later, in 1979, he marries musical collaborator Rosanne Cash and they begin a family. The records he produces with his wife prove more successful commercially than his own, yet Crowell is undaunted, proud of his role as her producer and as a songwriter of expanding scope, including a breakthrough pop/rock hit in Bob Seger’s version of “Shame On The Moon.” Crowell releases But What Will The Neighbors Think and a self-titled album, whose singles just scratch the Top 30. He leaves Warner Bros. and five years pass before he finds a new chance as a featured recording artist. Columbia Records releases Street Language, co-produced with Memphis keyboard legend Booker T. Jones, and though it consolidates his cult following, it languishes commercially. Had Crowell pursued a major label career a decade or so later, he’d never have survived the waiting game for hits, but widespread admiration for Crowell’s work and continued high expectations keep his label with him. And Columbia’s patience is rewarded when in 1988 Crowell’s album Diamonds & Dirt connects with the times in an uncanny way, producing five consecutive No.1 hits at country radio. It’s a stunning run of success that makes Rodney Crowell a rather sudden object of desire in the music business. “I experienced that adulation thing for a moment,” he reflects. “You’re in that perfect storm. People project this thing on you. I call it the Elvis syndrome.” He is old enough at the time to be wary. “If you accept that projection and start to cobble together an image of yourself based on other people’s longing - if you build that ego structure - you’re in trouble. Or I would be in trouble. The insincerity that started to show itself, I recognized as the enemy of art.” Thus, his approach to the business and radio grows aloof and, he admits, self-sabotaging. His next two albums for Columbia fail to achieve the heady highs of Diamonds & Dirt, and he is dropped from the label. A move to MCA records, under the care of old friend and iconic producer Tony Brown, produces two albums, but they achieve less than hoped. To make matters more complex, his marriage to Rosanne Cash unravels, and he has three daughters. He calls 1993 to 1995 the lowest point in his life and career. Renewal comes through time and largely stepping away from writing, recording and performing. He gets his kids through school. He dates and marries musician Claudia Church. “I think I was trying to give birth to a legitimate artist,” he says of the period. “I’d proven myself as a songwriter and producer but it took me until the end of that five year period until my voice sounded right to me. I just shut (the music business) down and lived.” The quiet time leads Crowell toward reflecting on and ultimately writing about his youth and his parents. He strikes up a relationship with acclaimed poet and memoirist Mary Karr, a fellow East Texan who teaches writing at Syracuse University. She encourages and coaches the work that will become “Chinaberry Sidewalks.” Meanwhile, Crowell’s memories take the form of songs as well, and when The Houston Kid is released on Sugar Hill Records (a label far removed from the radio-driven ecosystem of major label country music) the press hails it as Crowell’s comeback. It is character-rich and revealing, and it even includes a duet with Crowell’s idol and former fatherin-law Johnny Cash. Indeed the record presages a major new phase of Crowell’s career. Two more reflective, searching albums follow, and their thematic and musical coherence leads some critics to call them a trinity, though probably more in the Creole cooking, onions-peppers-celery sense than the father-son-holy ghost sense. Crowell records a fourth album of memoir-style songs, but he feels the ground has already been covered and he shelves it. To shake up his pattern he turns to canny roots artist Joe Henry as producer. Crowell takes his hand off the wheel and off the recording console. Instead of obsessing over every detail of the mix, he focuses on writing and performing in the studio. Then, “I said ‘see you guys – send me the album.’ And I got Sex & Gasoline in the mail. I put it on and said WOW this is great. Why did I wait so long? The only objectivity I brought to that was I was going to play and get out. And I think I really started to come into my own as a singer and guitar player on that record.” That he’s well into his 50s before granting himself credit as a fully realized singer speaks to the humility and the flavor of ambition that’s fueled Crowell’s career. As the 2000s progress, accumulated recognition of Rodney Crowell bring forth a series of accolades. But the work continues. He makes the album Kin as a writing collaboration with Mary Karr, on which a range of remarkable artists and friends take vocal turns, including Norah Jones, Vince Gill and Lucinda Williams. The collaborative ethic continues as he makes Old Yellow Moon, a long-awaited duet album with his old muse and friend Emmylou Harris. It is recognized as the Americana Music Association Album of the Year and their duo, elevated by an extensive and well-received tour, is also an AMA winner. With a new album titled Tarpaper Sky coming in the Spring of 2014, Rodney Crowell is in full voice and fully engaged in his musical present and future.

-

In a Nashville bookstore, to the tune of steam hissing from a latte machine and laptop taps of nearby browsers, she speaks in a low voice, yet communicates urgently. Her voice never rises. Her music never rattles rafters or crashes like cymbals toward the high notes in a power chorus. Her tempos shuffle and trudge more than they dash.

And her songs? They're about as idiosyncratic as anything in the wide world of "popular music." They're painfully personal, especially on Trouble and Love. Yet they somehow infiltrate the souls of her listeners, no matter how different the paths they've followed through their lives.

Those songs weren't so much written as harvested by Gauthier. Though she lives not far from the hit-making mills of Music Row, she admits to knowing nothing about how to write on command. She says, "I have to be called to write. The call comes from somewhere I don't understand, but I know it when I hear it."

That call first came to her a long time ago. Her life to that point had led her to extremes, plenty of negatives and a few brilliant bright spots. An adopted child, who became a teenage runaway, she found her first shelter among addicts and Drag Queens. Eventually she achieved renown as a chef even while balancing the running of her restaurant with the demands of addiction to heroin.

Two more successful restaurants, an escalating addiction, and a subsequent arrest, led her into sobriety. All that was rehearsal for what to follow, when she wrote her first song in her mid-thirties.

From that point, Gauthier channeled a long line of works, almost all of them eloquent in their insight, burnished by her writing technique. A core of devotees came to await each next release. Their wait ends, for now, with Trouble and Love.

This time, Gauthier's songs rise from what she describes as an especially dark period. "I started the process in a lot of grief," she explains. "I'd lost a lot. So the first batch of songs was just too sad. It was like walking too close to the fire. I had to back off from it. The truth is that when you're in the amount of grief I was in, it's an altered state. Life is not that. You go through that. We human beings have this built-in healing mechanism that's always pushing us toward life. I didn't want to write just darkness, because that's not the truth. I had to write through the darkness to get to the truth. Writing helped me back onto my feet again. This record is about getting to a new normal. It's a transformation record."

The heart of that transformation, beating within Trouble and Love, is love. But it’s not the kind of love that's celebrated on pop charts. In those tunes, love is its own end; the story stops as the giddiness sets in, with no hint of what may follow. Gauthier knows better; she has the scars to prove it.

"For me, love has been a real challenge," she admits. "Attachment has been a challenge. This record is about losing an attachment I actually made. The loss of it was devastating because I hadn't fully attached before to anyone. The good news is that I can. The even better news is that I can, and I can lose, and live. Not only do I live, but I've got a strength that I never had before."

Trouble and Love would fall or rise on the question of whether it crystalizes Gauthier's experience and conveys it to those who want to feel it, as if the poetry of her lyric can mirror and illuminate what they too have gone through. To help make this happen, she invited a small group of singers and musicians into Nashville's Skaggs Place Studio, each one chosen because of his or her ability to find the heart of the song. No one was given a lead sheet or an advance demo or even headphones. The backup vocals were invented on the spot. The microphones were vintage, and the songs were cut live, to tape. Everyone stood together in the room, playing to what they heard in the lyric as well as from what was going on in the moment.

"I took away everything that musicians lean on to feel invulnerable," she explains.

All they had to work with was a brief rundown of each song from Gauthier in the control room, right before the tape rolled. "I wanted them to feel it in real time," she continues. "You don't want to sound real with songs like this. You want to be real. That’s what I strive for as a writer, and that's what we got in the playing."

Feeling their way through the process, these extraordinary participants -- guitarist Guthrie Trapp, keyboardist Jimmy Wallace, bassist Viktor Krauss, drummer Lynn Williams and singers Beth Nielsen Chapman, Ashley Cleveland and Darrell Scott, Siobhan Kennedy and The McCrary Sisters -- probed and then brought life to Gauthier's compositions. In their hands, and in her fearless vocals, the songs resonate like tolling bells.

We hear "a body's but a prison when the soul's a refugee" in Oh Soul. The last embers of affection flicker and die on When a Woman Goes Cold, (“Scorched earth cannot burn.”) "A million miles from our first kiss, how does love turn into this?" is just one of the bitter riddles posed in False From True. Irony colors the chorus of Worthy: "Worthy, worthy what a thing to claim. Worthy, worthy, ashes into flame."

This is deep and dangerous poetry, and Gauthier leads us through it with relentless candor. Yet tenderness is always near, enough to keep us engaged through the final track, "Another Train."

"I wrote that one in England during a long, long tour," she remembers. There was a sign at a station: There'll be another train at 14:02.' So I started working with 'another train.' The song evolved. It doesn't start the way it ends. It zigged and it zagged. I let it talk to me. It's so interesting, because when I saw 'another train,' boom, that whole story was in there -- but I had to go find it. I had to dig, like an archaeologist."

In the very last line of the song is the benedictory thought of the entire album. "Another Train" bathes all of what preceded it in a glimmer of hope. It a fantastically concise and powerful ending — and entirely intentional — “There’ll be another train.”

"This album reflects a total human experience. Love, loss, and a life transformed." Gauthier sums up. "It's not a random collection of songs. This record is a story. It's about trust and faith and believing that there's a plan and a flow. And the flow is where the good stuff is because there's wisdom in the flow. At the core, we're all cut from the same cloth-- the same dreams, the same brokenness, the same desire for companionship and family and home. Yeah, we all have that. And if I don't go deep enough into that, it's a problem.

"There's no such thing as going too deep."

-